When the Molinaroli brothers push off from the Folly Beach boat ramp, they are unbothered by the summer storm rumbling in the distance. It’s 9 a.m., the tide is high — the weather is almost cool until the clouds blow through — and as Ray Molinaroli steers the boat into the Lowcountry marsh, Alex and Carl shout over the slapping surf.

They reminisce about old friends, childhood pranks, days spent with a cast and seine net in the creeks behind their home. Ray remembers catching blue crab, spreading them out on newspaper and cracking the claws. Carl recounts the time he, Alex and their dachshund hiked clear across the marsh from their house in James Island to Morris Island.

Molinaroli? You’re forgiven if you don’t know the name. But if you’re a University of South Carolina Gamecock, you’ll hear it a lot in the years ahead — especially down at the College of Engineering and Computing. Or, scratch that: the Molinaroli College of Engineering and Computing.

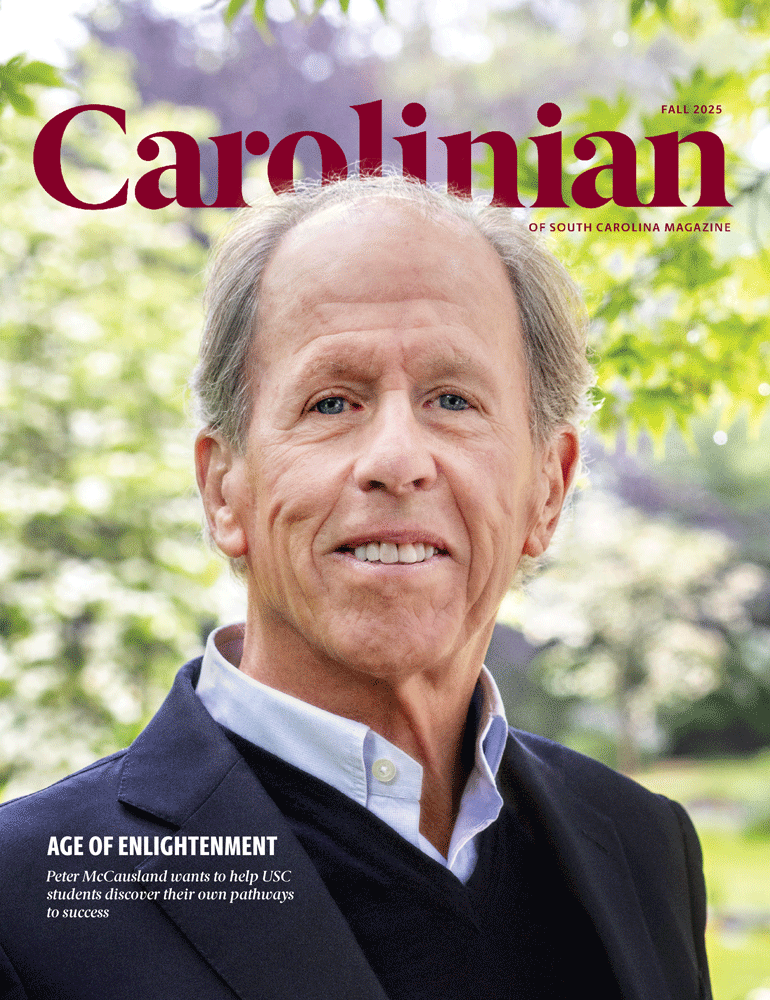

In May, the oldest brother — Alex Molinaroli, ’83, South Carolina Honors College, former CEO of Johnson Controls — and his wife, Kristin, donated $30 million to the college that now bears his family’s name. But the brothers aren’t talking philanthropy at the moment. They’re on their way to lunch at Bowens Island, a rustic, graffiti-covered oyster shack on cinder blocks that’s been popular with locals like the Molinarolis for decades.

Alex picks up Carl’s story about hiking across the marsh. The same terrain they’re revisiting now is a maze of creeks and channels through dense marsh grass. At high tide, the boys could zigzag through in their flat-bottomed jon boat. At low tide, the marsh became pluff mud. It was a difficult journey on foot, but the boys forged ahead. “I think we just wanted to see how far we could go,” Alex says.

Fifty years later, Alex has gone far indeed — in business but also geographically. Carl stayed in Charleston, where he engineers and repairs electronic circuits for the military, and younger brother Ray lives just up the road in Summerville, where he works as an engineer with the South Carolina Department of Transportation. Alex, the oldest Molinaroli, now retired, splits time between Wisconsin and Florida.

Alex has been back in South Carolina a few times this spring and summer for events surrounding the gift announcement, but this trip is about family. After all, the gift was made in the family name. He is very particular about that. As the boat approaches the dock at Bowens Island, he underscores the point.

“It’s our name,” he says. “Somebody will see it one day and say, ‘I don’t know who that dude was or who those people were’— they may not know who Alex Molinaroli was — but our family’s name will still be there, and that’s kind of cool. And I have to say I’m OK with it. I want the fuss to be over, but I’m OK with it.”

Founded in Milwaukee in 1885, Johnson Controls started out making temperature control systems, then gradually expanded operations internationally to include fire, HVAC and security systems as well as the production of automotive batteries and seating. By the time Alex Molinaroli joined their Columbia office as a sales engineer after graduation, the company was already a global leader in building technology and efficiency.

And the position was a good fit. Alex was as drawn to the business side of engineering as he was to the details of a purely technical engineering role. “I didn’t want to work every day lost in a sea of cubicles doing drawings,” he says. “I knew that wasn’t me. That’s just not how I’m put together.”

Meanwhile, working in Columbia, a short drive from his new alma mater, presented opportunities. The College of Engineering was housed in Sumwalt College while Alex was in school, but in 1987 the Swearingen Engineering Center opened its doors. Alex had already been promoted to sales manager in the Nashville office by then, but before he left, he brokered the contract with USC to install the company’s technology in the new building.

It was a steady climb from there. After sales and general management positions in Atlanta and Houston, he moved to Milwaukee in 1998 to be the company’s vice president of sales and marketing for North America and then for the Controls Group. In 2004, he became building efficiency vice president and general manager of North America Systems and the Middle East. Three years later he was named president of the company’s battery business, Power Solutions. Six years after that he was CEO.

“When Alex got the job in Milwaukee, I said, ‘You know what? I think Alex is going to be CEO,” Carl says. Alex demurs: “Well, I was still a long way from there.” “But you did take a jump,” says Ray.

“In any successful career, you’re not going to get to that place unless at some point in your career you do something not linear,” says Alex. “For me, the move to Milwaukee was probably it.”

Maybe. Or maybe the electrical and computer engineering graduate is just hardwired to do things his way. Example: A couple years into college, he landed a job at the Checker Yellow Cab company and ended up running the operation. He then took a year off from school, borrowed some money and purchased six cabs.

It wasn’t what he wanted to do for the rest of his life — “I made good money,” Alex says, “but soon I realized running cabs probably wasn’t the career for me” — but the episode says something about his nose for business and his willingness to chart his own course.

Alex and Kristin’s gift to the College of Engineering and Computing came as a shock to Ray and Carl, neither of whom ever imagined they might one day see the family name on the college that has educated so many of them. To date, six Molinarolis have engineering degrees from USC: Alex, Ray and their father, Adrian; Alex's uncle, Remo, and cousins Charles and Marion. Alex’s stepson, Derek, is currently studying civil engineering.

“I made it clear that I didn’t want my gift to result in a new building, but I did want a plan for the future. As the college grows, we have a plan for how to grow into an ‘Engineering District’ that will be a destination for our students — a place to collaborate and not just take a class, but a place for our engineering students to call home.”

It’s an impressive Gamecock legacy, but the family’s story began with patriarch Alessandro Molinaroli, who immigrated to the U.S. from Northern Italy in 1906. A stonemason by trade, Alessandro eventually settled in Columbia’s Elmwood Park neighborhood, where there was a small but thriving Italian American community.

Adrian was the immigrant couple’s fourth child, born when Alessandro was in his 40s and his wife was not much younger. When Alessandro died at 52, Adrian was still in grade school, so his older brother Remo, already 18 when Adrian was born, stepped in as a father figure. Uncle Remo would play an important role in the Molinaroli boys’ lives, too.

Remo was the first in the family to become an engineer, graduating with a bachelor’s in civil engineering in 1934, one year after his wife, Eleanora — Aunt Nora, as the Molinaroli boys called her — earned a chemistry degree from the university.

“Uncle Remo was kind of a Renaissance man,” says Alex. “He was first cellist in the Charleston Symphony. I remember going to the Cistern at the College of Charleston and watching him.”

Adrian had also watched Remo, following in his big brother’s footsteps to USC and — thanks to the GI Bill —earning his civil engineering degree from USC in 1951. In the years prior to Remo’s death, Adrian had the pleasure of working alongside him. The Molinarolis seemed to possess a natural aptitude for engineering.

That same aptitude got passed down to Alex and his brothers. While his boys were growing up, Adrian worked as the resident officer in charge of Navy and Air Force construction at the Charleston Navy Yard. He never discussed his projects — “My dad died with a lot of words left,” Alex jokes — but he taught by example.

“If you threw a bunch of parts on the floor,” says Ray, “my father could figure out what it was, put it together and make it work.” The brothers nod in agreement. “And if he couldn’t,” says Alex, “Carl could for sure.”

And while Adrian may not have been a talker, he was a good dad. He built things for his boys — a pool for their James Island neighborhood and a saltwater lake on Uncle Remo’s land near Edisto, but also an idyllic, middle-class life. The son of an immigrant had achieved the American dream.

Leaving Bowens Island, the Molinaroli brothers goof around and tease each other, but they are always quick to sing each other’s praises. Asked what makes their older brother tick, Ray and Carl agree on one thing: Their big brother likes to win.

Alex wouldn’t bring it up himself, but he grins when Carl reminds him of the time he won a dribble-pass-shoot competition during halftime at a USC basketball game. “See, that’s the ‘I like to win’ thing,” Ray says with a laugh. “This was 50-plus years ago and he’s reveling in it still.”

But in Alex’s book, individual wins are nothing compared to team wins. That mindset helped guide his decision to invest in his alma mater. It’s critical to help future engineers prepare for the evolving career landscape, he says, and he has a vision for how USC can make that happen.

“I made it clear that I didn’t want my gift to result in a new building, but I did want a plan for the future,” he says. “As the college grows, we have a plan for how to grow into an ‘Engineering District’ that will be a destination for our students — a place to collaborate and not just take a class, but a place for our engineering students to call home.”

As the boat pushes off from the dock, the college’s new namesake explains his vision, which extends far beyond enhancing campus.

South Carolina is at a watershed moment, he says. Employment and economic growth have been strong in recent years, due in part to significant growth in the advanced manufacturing sector. By developing a new industrial engineering program, the Molinaroli College of Engineering and Computing will help prepare South Carolina to meet the resulting workforce demands.

Another new program, advanced energy systems and electrification, will add to and leverage some things the college already does well — battery research and nuclear engineering. The hope is to provide jobs to support battery research and manufacturing and help revitalize growth prospects in nuclear power generation.

“Whether it’s around traditional or renewable sources of energy, it’s what the next-generation student wants to do and what our state needs,” he says. “And it’s an opportunity to differentiate ourselves.”

Highly specialized programs are just the beginning, though. The college’s new plan also calls for increased collaboration with USC’s top-ranked Darla Moore School of Business, investments in faculty and student recruitment, transformative industry partnerships along with the development of applied artificial intelligence and a continued investment in USC’s aerospace program. These efforts won’t just drive innovation and support economic growth in the Palmetto State; they will establish the college as one of the leading educational and research institutions in the region.

“The first thing we must do is get out of the mindset that we want to be the best in South Carolina, because that’s a fool’s errand,” Alex says. “That’s a ‘big-fish, small-pond game.’ This pond no longer has borders. Prospective students don’t have borders. Companies don’t have borders. Technology has no borders. If we want to compete — and compete for the best students — we must be able to compete with the organizations and institutions who are the leaders in all these activities.”

Alex is a realist. “The university and the Molinaroli College of Engineering and Computing can’t be the best at everything,” he explains, “but it can be great in specific high-impact areas. It’s about focus, harnessing the talent that’s already in place and building on it.”

The Molinaroli brothers stand at the front of the boat. Ray, not Alex, is the captain here, but all three brothers help guide the family’s journey. Success in anything is about teamwork.

“The most important thing I’ve learned in my life’s journey is that nothing worthwhile is likely accomplished on your own,” Alex says. “And if you try, it’s going to take you longer and you won’t do it as well. But if you can get people to help you, and you’re a little vulnerable, and you let others be a part of your success, you’ll do a lot better. Fortunately for me, I learned that lesson very early. A lot of people helped me along the way.”